Cult Behaviour

How cults control and influence

By an international group of people with lived experience and professionals passionate about harm reduction

This article does not reflect the experience of all cult survivors, as the diversity and richness of these experiences are as vast as the people who have been victims (and grown to be survivors) of cults. This article has been written with the literature and the first-hand experiences of cult survivors in mind, having gone through a grey literature peer review process.

If a group is named in this blog, it does not mean that SOL perceives the group to be a cult, or that they have violated laws in relation Íto abuse, violence, or coercion. The information contained herein is publicly available and has been written for educational purposes, and not with the intent of exposing or defaming. We encourage all viewers and participants to consider the practices of all groups, irrespective of the label ‘cult’ – and to inquire into the ethics of groups, whether that be religious, spiritual, philosophical, social, corporate, or otherwise.

“Virtually everyone leaves Utopia after a time. The quick and hearty do not necessarily defect early, nor is it always the witless who linger on. One leaves when he has gained what he came for, when his commitment is exhausted, when it is no longer necessary to sort through the breviary of questions that concern his freedom.”

- Tom Patton

Foreword to W.F Olin’s Escape from Utopia

In our quest to understand the dynamics of human groups, it is crucial to differentiate between groups that fulfil essential functions and those that exhibit cult-like characteristics. In this blog post, we will embark on a journey to explore several key aspects related to cults. We will delve into the definition of a cult and the profound influence it can have on individuals. Additionally, we will examine the dynamics of cult leadership and control, effective methods for identifying cultic behaviour and leadership (including within the psychedelic and corporate spheres), and ways to provide support to individuals who are considering leaving or have already left a cult. Lastly, we will discuss important considerations for those who wish to speak out about cults or cultic behaviour within the Australian legal framework. Join us as we navigate these topics and shed light on the intricate world of cults.

What are cults?

What are cults?

Have you ever heard the word “cult” and wondered what it really means? Well, let’s break it down for you in simpler terms. The word “cult” comes from the Latin word “cultus,” which means ‘to worship’ (Agetue & Ogodu, 2022, p.33).

Now, here’s the thing: there isn’t just one clear definition of cults (Kern & Jungbauer, 2022). Different experts have different ideas about what exactly makes a group a cult. Some definitions describe cults as having extreme ideologies rooted in religious beliefs. Others focus on how cults control their members, suppress their individuality, and demand obedience to the leader’s norms, values, beliefs, and causes (Kern & Jungbauer, 2022; Pignotti, 2000).

In this blog post, we’ll use the latter definition. We believe that cults don’t have to be religious in nature. They can also be found in various types of entities, like community and sporting groups, orphanages, and welfare services (Tilgner et al., 2015).

According to the International Cultic Studies Association (n.d.), defining a cult can be quite challenging. However, they do agree that cults always involve control, manipulation, abuse, exploitation, and place high demands on their members. To put it simply, as Pignotti (2000, p.201) pointedly states:

‘Cults are best defined in terms of their deeds rather than their creeds’.

It is estimated that half a million Australians are affected by cults (Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, 2000). The belief system and philosophy of cults are not necessarily extreme, as some are united under a cause that may seem worthy and relevant. However, the methods employed to achieve this cause can be problematic and subject to the cult leader’s directives, often involving control, power, influence, exploitation, or coercion (Ellwood, 1986; Meyer, 2016; Young & Griffith, 1992). Cult leaders can possess charismatic, authoritarian, and manipulative qualities (Lifton, 1961). They require members to conform to the norms and beliefs of the cult and commit to its cause. The purpose driving a cult can be religious, philosophical, or aimed at providing answers to significant societal issues (Meyer, 2016). Cults act as a collective (Best et al., 2018), and the shared dedication to the group’s cause strengthens internal bonds and fosters feelings of social connectedness among its members (Kern & Jungbauer, 2022; Galanter, 1999).

What can a cult look like?

- Members of the group are encouraged into unwavering faith in the group and its cause (Kern & Jungbauer, 2022).

- Behaviour or intentions that aren’t displayed honestly or openly.

- People within the group strongly defend the group, its identity, values and any cause it represents to anyone who disagrees with their position.

- People outside of the group can be perceived as dangerous, capable of undermining the group in some way or living in opposition to the aims of the group (Tajfel and Turner, 2004).

- People within the cult are encouraged to stay away from outsiders (Collins, 2020) and can be forbidden from having relationships or friendships if the people don’t belong to the group (Collins, 2020).

- People who leave the group can be outcasted, losing family, friends and relationships.

- People who leave (or are thinking about leaving) can have their reputation, livelihood, or relationships threatened.

- The group and its leader might have tactics to isolate and scare a person who considers leaving, and to prevent them from speaking out against the group.

How cults control: Understanding the methods

Cults exert various forms of control over their members, which can range from moderate to extreme and encompass different aspects of their lives. These control mechanisms include psychological, economic, social, physical, and spiritual means. Let’s explore each of these methods in more detail.

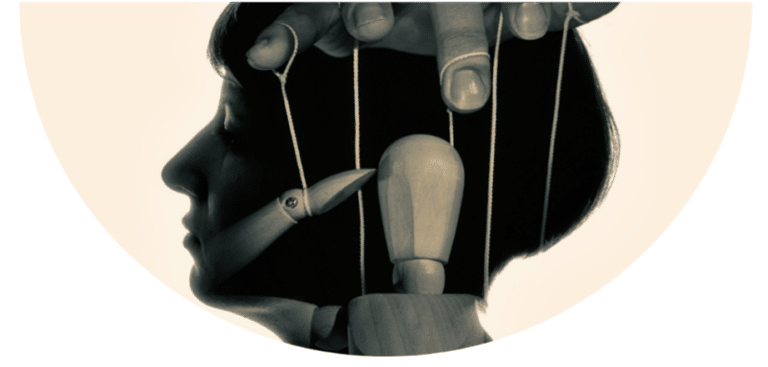

Psychological Control

Cults employ coercive control, a form of psychological abuse, which involves manipulating individuals through covert tactics. This manipulation can leave individuals feeling confused, seeking approval from the manipulative cult leader(s), and blaming themselves when they displease the leader. Coercive control often includes gaslighting (making someone question their own reality), loyalty tests, and the cult leader showing excessive attention or affection that is quickly withdrawn when the member acts against their wishes (

, 2022). It may also involve a gradual process of removing doubt and self-questioning (Lifton,1961).

Economical control

Cults may attempt to control how members spend their money, and where members live.

People may be asked to provide money or other assets to the cult, under the guise of forwarding the cause (Steel, 2022, pg.89-95).

Physical Control

Physical and sexual abuse can occur within cults as a means to instil fear, loyalty, or confusion. Such abuse aims to diminish an individual’s self-worth and increase their dependence on the cult or to serve some aim put forward by the cult leader. Examples of physical abuse include sleep and food deprivation, free and intense labour without pay or recognition, acts or threats of violence, and denying access to healthcare (Steel, 2022, pg. 124-132).

Social Control

Cults often seek to isolate individuals from their friends, family, and intimate relationships (Steel, 2022, pg.69). These external relationships are viewed as threats or distractions by the cult or are considered unworthy or dangerous to the cult’s mission. Information restrictions may also be imposed, limiting access to media, news, books, and radio (Steel, 2022, pg. 85-89). Cults emphasise absolute trust within the group, discouraging any doubt. Group members may be encouraged to divulge all their secrets, transgressions, thoughts, and doubts to leaders or fellow members, leading to a blurring of boundaries between the individual’s private inner life and the group (Lifton, 1961). These secrets can later be used against an individual if they decide to leave the group.

Spiritual Control

Cults employ manipulation using the threat that non-compliance with the cult leader’s demands will have consequences for one’s spiritual or philosophical beliefs. These consequences may involve exclusion from entering a transcendent state or Armageddon coming to Earth (Steel, 2022, pg. 96-98). Extended periods of rituals, chanting, or altered states of consciousness, such as through the use of psychedelics, may also be used as methods of spiritual control (Lalich & Tobias, 2006; Galanter, 1999). Spiritual control may be religious, and rules may be outlined in a doctrine or text that is taken with extreme literality and fundamentalism (Lifton, 1961).

These methods of control can lead individuals to become alienated from their sense of self (Rajesh et al., 2022), initiating a dependency that grows over time and eventually results in deindividuation. Deindividuation refers to the process whereby individuals in a group gradually lose their self-awareness, adopting a “group awareness” in its place. The cult members encourage the disintegration of individual identity, replacing it with a group identity that aligns with the cult’s norms, values, and mission (Kern & Jungbauer, 2022).

Techniques used by cult leaders

Cult leaders employ various techniques to exert control over their followers and advance their ideologies (Best et al., 2018). They establish a mission or purpose that forms the basis of their ideology, which is determined by the leader and enforced through a process of indoctrination involving both the leader and the members (Meyer, 2016). The leader creates the cause, promotes propaganda within the cult, and uses it to minimize individual decision-making. Ultimately, the leader’s goal is to gain control over what is said, done, and who does what within the cult (Oakes, 1997). Sometimes, cult leaders believe that their means are justified, consider their behaviour helpful rather than harmful, or view those who oppose them as the problem.

Cult leaders often exhibit traits of grandiose narcissism (O’Reilly & Chatman, 2020), sociopathy, psychopathy, and/or authoritarian personality types (Tilgner et al., 2015). They often have an inflated sense of importance and confidence, and are influentially extroverted, often appearing as extremely charismatic (O’Reilly & Chatman, 2020; Lalich & Tobias, 2006). They can mask their ability to manipulate with charm, reading people, identifying weaknesses and vulnerabilities, and assessing what is important to people to connect with them (Oakes, 1997; Tilgner et al., 2015; Lalich & Tobias, 2006). Using their emotional intelligence, cult leaders exploit people for personal gain, displaying little-to-no remorse due to their low empathy and belief in the justification of their actions (O’Reilly & Chatman, 2020; Kriegman & Solomon, 1985). They establish connections with individuals to gather the information that can later be used against them, including personal threats involving physical harm or the exposure of confidential secrets that could have repercussions for the group member.

Cult leaders can be motivated by money, sex, power, or a combination of these factors (Lalich & Tobias, 2006). They require obedience, belief, and commitment from their followers, often employing subtle tactics that exploit the insecurities, fears, desires, and dreams of individuals. Sometimes, leaders present themselves as knowledgeable, qualified, or living a lifestyle that implies their worthiness to lead the cause, while in other cases, their grandiosity and self-importance create a false image that is later revealed to be inconsistent or untrue. Cult leaders reward devotion and punish those who challenge them by withholding attention, or affection, or by displaying aggression and hostility (Oakes, 1997; O’Reilly & Chatman, 2020; Kriegman & Solomon, 1985). If they perceive individuals as a threat to the cult, the leader may tighten control measures (Maccoby, 2004), leading to increased hostility and making it more dangerous for members to leave the cult. Leaders also encourage members to spy on and report on one another (Tilgner et al., 2015), often suggesting that certain members pose a threat to the group. Within the cult, individual doubts are suppressed both internally and among group members, as group cohesion overrides personal desires and feelings.

As more people believe in and support the narcissistic cult leader, their power grows, leading to more spontaneous and impulsive actions and ideas. As the leader’s confidence in themselves grows, so does that of their followers (Maccoby, 2004; O’Reilly & Chatman, 2020). Oakes (1997) emphasizes two key aspects of a cult leader’s influence: the first is the ability to provide a sense of acceptance, which fosters trust and devotion, and the second is the practical solutions they offer that add value to the lives of their followers. Survivors of cults often describe their initial interaction with the cult leader as feeling genuinely seen, heard, or understood. However, for narcissistic leaders, all conversations are transactional, and although they may occasionally show compassion and understanding, they lack empathy and display compassion with the intention of manipulating others for personal gain.

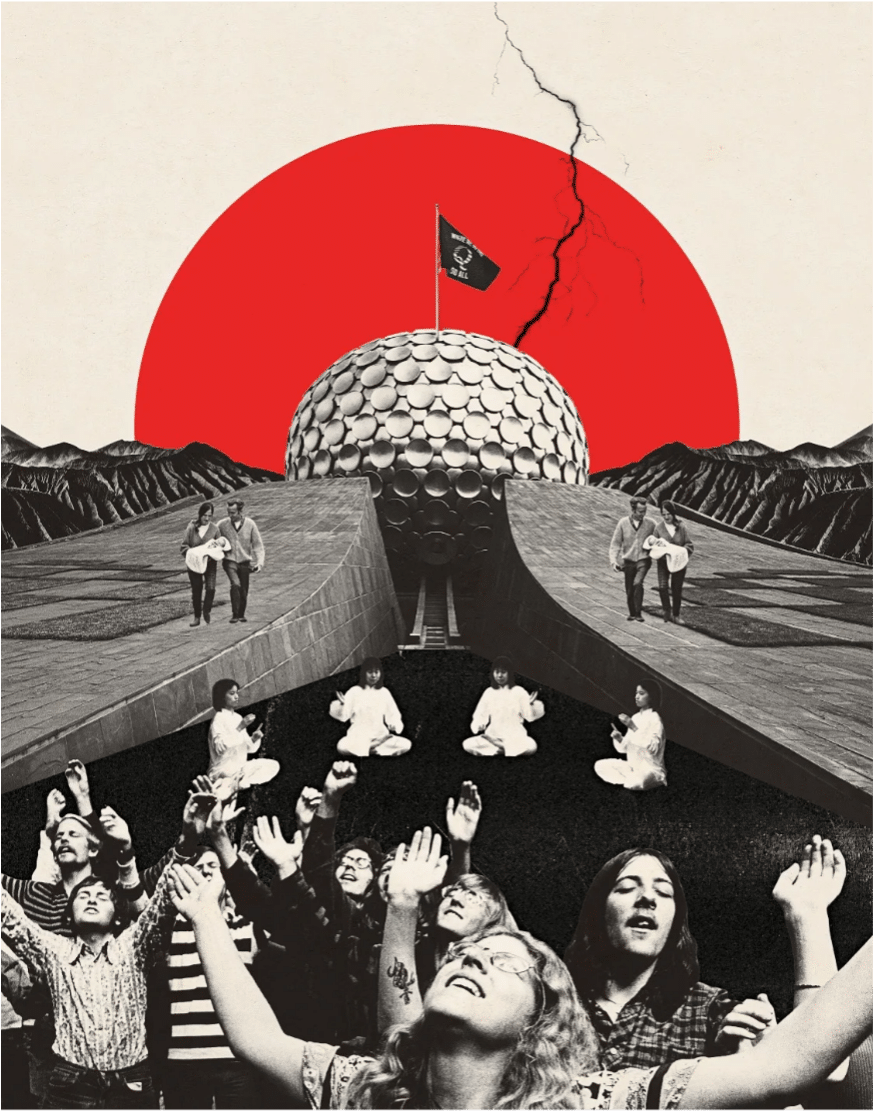

How cults influence people and why people join cults

Cults have a profound impact on individuals, both in terms of recruitment and influence. While some people are born into cults as second-generation members, others are recruited or unknowingly join a group that exhibits cult-like behaviour. Understanding the reasons why people join cults can help shed light on this complex phenomenon.

Second-generation members, who are born into cults, often face significant challenges when it comes to leaving. They have limited external support and understanding of life outside the cult’s confines (Tilgner et al., 2015). On the other hand, individuals who are recruited into cults may be vulnerable members of society who are experiencing crises, unrest, change, or transition (Steel, 2022, pg.42; Tilgner et al., 2015; Galanter, 1999). These vulnerabilities could stem from recent divorces, relocations, personal or professional losses, or individuals with caring and compassionate personalities who may be more susceptible to cult dynamics. Loneliness and the desire for belonging and connection also play a significant role (Kern & Jungbauer, 2022). Cults recognise these needs and exploit them for their cause. It is important to note that individuals who engage in a cult should not be blamed; they often become victims of control, peer pressure tactics, and psychological abuse while being in a heightened state of vulnerability.

Before joining a cult, many members were actively seeking something meaningful. Upon encountering the cult leader, they often identify this “something” in the leader, whether it be a cause, a movement, or shared values (Oakes, 1997). Therefore, those who join a cult may not always be in a state of crisis but rather in a state of “seeking.” The cult and its leader provide hope, a newfound sense of meaning, and purpose to these individuals, leading them to feel motivated, hopeful, and dedicated to the group (Meyer, 2016).

Cults employ various methods to recruit individuals. They may invite them to special functions, classes, or activities, often luring them with promises of meaningful returns such as promotions, opportunities within the cult or organization, or even offering psychedelic substances. Propaganda tactics used by cults can involve praying, lecturing, meditation, sleep deprivation, manufacturing crises, preying on fears, or providing answers to important life and philosophical questions (Dittmann, 2002; Best et al., 2018; Kern & Jungbauer, 2022). Once individuals accept the propaganda, they are gradually initiated into the group’s processes and way of thinking, while rejecting outside perspectives (Best et al., 2018). Cult members bolster the positive identity of the group when the individual questions its processes. The group collectively provides answers, pushing the individual towards deindividuation, where personal characteristics, feelings, motives, and desires are lost (Best et al., 2018).

Throughout this process, cults may employ guilt, shame, or fear to influence and persuade recruits (Lalich & Tobias, 2006). Emotional arguments are used to convince individuals to adopt the group’s way of thinking (Cialdini, 2017, pg.91). Cult members may also encourage conformity to the group’s norms. The desire for social acceptance drives new recruits to conform if they believe that the cause and the group offer meaningful purpose and connection.

Cults and Psychedelics: Understanding their influence

Cults, as described by Rajesh et al. (2022), are groups that aim to induce powerful subjective experiences to open the mind to extreme beliefs. On the other hand, psychedelics have the potential to foster a sense of belonging and increase a person’s openness to new perspectives and ways of thinking. While psychedelics can be a valuable tool in therapeutic and culturally significant rites of passage, they can also be detrimental when used to manipulate and transmit unverified beliefs to individuals (Rajesh et al., 2022). Galanter (1999) points out that altered states of consciousness, including those induced by psychedelics, can shape the attitudes of cult members and make them more receptive to accepting new ways of being and seeing the world. Unfortunately, some charismatic cult leaders, such as Charles Manson and Howard Whitaker, have exploited psychedelics to recruit, manipulate, and control individuals (Rajesh et al., 2022). When psychedelics are provided by a cult leader, the leader’s perceived power and influence can become amplified, leading cult members to regard them as god-like figures.

Although the exact extent of psychedelics’ impact on psychological persuasion remains uncertain and scientifically unexplored (Dupuis, 2021), it is widely acknowledged that these substances can increase a person’s suggestibility. When interpreting a psychedelic experience, the account of the individual can be shaped by the influence of the environment and the process of meaning-making that the individual and others may apply to the experience. Therefore, it is crucial for anyone engaging in psychedelics to do so within a safe and supportive environment, considering the people around them and the beliefs and safety practices of the facilitators.

Within the psychedelic community, it is important to be aware of the phenomenon known as “spiritual bypassing.” This refers to individuals using their spirituality or belief in psychedelics as a means to excuse unethical behaviour. Examples of this could include marketing materials that portray psychedelics as ultimate healers or solutions for all problems, companies with leaders displaying narcissistic traits, or charismatic group leaders offering psychedelics. Accountability, transparency, integrity and listening to elders in this space is of the utmost importance.

Leaving a Cult and Supporting Loved Ones: Recovery and Speaking Out

Leaving a cult can be an extremely daunting and challenging process. It involves severing ties with the cause, social connections, and even one’s own identity to reintegrate into the outside world (Coates, 2010). This can be especially difficult when family and friends remain in the cult or when external resources and support are scarce (Tilgner et al., 2015).

People leaving cults may experience a wide range of emotional and psychological disturbances and they may have experienced psychological, physical, or sexual abuse (Tilgner et al., 2015). Feelings of guilt, fear, anger, betrayal, grief, paranoia, loss and self-blame are common (Pignotti, 2000; Coates, 2010). Additionally, survivors may be diagnosed with mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, panic attacks, and dissociation (Coates, 2010). Leaving a cult can also lead to challenges like impaired memory, dependency issues, loneliness, indecisiveness, and difficulty trusting oneself or forming opinions (Collins, 2020; Burke, 2006; Buxant & Saroglou, 2008; Kern & Jungbauer, 2022). It may be hard to break free from the conditioning they experienced during their time in the cult (Collins, 2020; Burke, 2006; Buxant & Saroglou, 2008; Kern & Jungbauer, 2022). Some people don’t have the resources or support to leave the cult, they fear functioning in the outside world, or they can no longer recognise an individual sense of identity (Steel, 2022, pg.228). Limited life skills, finances, career opportunities, and restricted access to mainstream education can further complicate the process, especially for second-generation members (Tilgner et al., 2015; Steel, 2022, 185-190).

It’s important for individuals leaving a cult to know that help is available, and with time, they can reintegrate into society, regain independence, and rediscover their identity. Even though the journey may be challenging, it can lead to positive and lasting changes, known as post-traumatic growth (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). Post-traumatic growth might look like greater appreciation for life, increased personal strength, changed priorities and enriching personal relationships, and spiritual and existential dynamics (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). Post-traumatic growth doesn’t undermine the severity of the suffering experienced but recognizes the transformative power of moving through suffering. Many survivors use their experiences to develop stronger boundaries, assess risks, advocate for self-agency, and build healthy, diverse relationships that value individuality and non-conformity.

If you are supporting a loved one involved in a cult, it’s essential to remain non-judgmental, patient, and supportive. Avoid pressuring them to disclose details of their experiences before they are ready. Remember that survivors may feel immense shame and guilt, and harbour feelings of ‘how could I be so stupid’ – recognise that this individual has been subjected to manipulation by a group and indoctrinated Encourage them to share their experiences at their own pace, actively listen, and suggest seeking support from trained professionals.

Speaking out about cultic behaviour in company organisations

“It has been said that… secrecy is no longer acceptable; too many lives and livelihoods have been lost or destroyed because a whistle could not be blown. But too often the voice of the honest worker or citizen has been drowned out by the abusive, unaccountable bosses. Invariably, staying silent was the only option. Creating a safe alternative to silence represents a difficult challenge, legally and culturally; separating the message from the messenger is still obstructed by vested interests; deeply ingrained sociological habits and attitudes, and by the limitations of the law (Kennedy, 2004:, 10).”

Whistleblowing plays an important role in exposing misconduct within organizations. Under Australian law, a whistleblower is defined as someone who witnesses misconduct while being an employee or former employee of an organization and reports it to the appropriate authorised person. Misconduct can include illegal activities or unethical business practices. However, it’s important to note that not all reports are protected under Australian law.

Whistleblowers must report the misconduct to specific individuals or entities, such as senior representatives within the company, lawyers, whistleblowing hotlines, the Australian Security and Investment Commission, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority, or the police. The Australian law does not protect anyone making disclosures about company misconduct outside of these representatives, including to social media. If you were complicit or directly involved in the misconduct, Australian law does not protect you, regardless of your report. However, your cooperation may be considered during the proceedings. There are certain circumstances where a person may disclose to a journalist or parliamentarian in Australia, namely, it must be in the ‘public interest’ or considered an ‘emergency disclosure’.

See the following links for further information about whistleblowing in corporations in Australia, the criteria for making public disclosures, and what circumstances you are covered under the law.

For further information about considerations in speaking out as a whistle-blower please refer to the following PDF:

Whistleblowers who speak out about misconduct may face retaliation from the organisation, this is especially true for whistle-blowers who hold less power in the organisation (Dussuyer et al. 2018). Retaliation may be in the form of legal threats, attempts to defame or label wrongdoing on the individual, or reputational damage. Where the individual continues to work in the organisation the company may attempt to increase their workloads or demands on the individual – leading to burnout and psychological distress. In a study conducted by Dussuyer et al. (2018, p.8) whistleblowers reported feeling a lack of support, criticism, denial, blaming, and retaliation by management, and feelings of fear and actual bullying and harassment after making a disclosure. Some participants reported feeling isolated, and that attempts were made to sabotage their work or organisational reputation, as well as threats to their family or physical harm. While others suffered a loss of income from employment termination or psychological stress at the events leading to extended time off work. Interestingly, the study found

“None of those interviewed, be they whistleblowers or those who dealt with them, indicated that the protections offered by whistle-blower legislation were effective in preventing and deterring acts of retaliation and reprisal.” (Dussuyer et al., 2018)

If you are thinking of speaking out about misconduct speaking to a lawyer and getting supervision and psychological support is recommended. It is imperative that you understand if your disclosure will afford you any protections under whistle-blower laws.

Checklist: Identifying cult behaviour

This checklist has been adapted from https://culteducation.com/warningsigns.html. This checklist is not absolute, and every item does not need to be present in order for cult behaviour to be present.

- When you question the beliefs or practices of the group, are you made to feel as though you are a non-believer in the cause, that your faith has wavered, or that you are in some way causing a problem?

- Have you been asked to contribute financially to this group without knowledge of what this money achieves?

- When discussing those who do not belong to the group, do group members or leaders encourage you to think of those people as uneducated, dangerous, ignorant, mentally ill, or threats to the cause?

- Where individuals have left the group, do current members and the group leader(s) refer to these people as being problematic, dangerous, evil, or having committed some act of wrong-doing?

- Does the leader (s) of the group always appear right, uncontested by other group members or considered the source of all knowledge, expertise, and wisdom?

- Do group members get defensive, aggravated, or persecutory if the group leader (s) are questioned?

- Have former members of the group described it as controlling, manipulative, or ‘brain-washing’?

- Do you feel like you are not allowed to have relationships with others outside the group, or that by doing so, this would display to the group or its leader (s) that you are not committed to the cause?

- Do members of the group have identical or extremely similar beliefs, identities, mannerisms, and characteristics, often identical to the group leader (s)?

- Do the goals of the group and the leader (s) outweigh the personal goals, interests, and beliefs of the individuals within the group?

- Have you been encouraged to isolate yourself from people who do not belong to the group (such as friends, family members, or colleagues)?

- Do you know of people who have left the group and faced legal action or other forms of persecution or harassment?

Identifying accountability within an organisation and its means to silence

When considering the practices of an organisation, reflect on this quote, extracted from O’Reilly & Chatman (2020, p.15) “Narcissistic leaders are a significant, and perhaps even a growing organizational challenge…grandiose narcissists take outsized risks, exploit others, overclaim credit for success, blame others for failure, ignore the advice of experts, and are overconfident in their abilities and judgment. When they succeed, we focus on their successes and ignore the failure.”

- Is the organisation or group accountable to registration bodies, formal external review processes and clear and transparent reporting mechanisms?

- Are you afraid of speaking out due to fear of defamation and the members having financial means to silence you?

- Are the board and leaders in the organisation involved in conflicts of interest?

- Is the organisation structured to encourage diverse input and open dialogue, or is it structured to control and restrict open communication?

- Do the means used in the organisation justify the ends? Are they acting unethically but portraying their actions as necessary to achieve something important?

- Does the organisation conduct assessments on their workplace culture and ask for input from employees at all levels, and then act on this feedback?

- What professional boundaries exist within the organisation?

Engaging with whistle-blowers and people in positions of power: challenging oppression

This checklist has been compiled to encourage members of the public and those who know someone who has been engaged with a cult to show compassion, empathy, support, and solidarity with victim-survivors. We encourage people to reflect on the stigma they may associate with those who have become involved with cults. Of utmost importance is to critically reflect on any slander produced by cult groups about the victim-survivor, and to acknowledge this is a widespread tactic used by cult groups to silence people from telling their story; to stand with someone in the face of oppressive forces is to show courage, but most importantly, it supports the victim-survivor in their courage to stand up to powerful forces with the means to silence, to say, enough is enough. We salute and pay our deepest respects to any individual who has spoken out about cult behaviours, and we equally salute those who have not spoken out, may your journey lead you to a place of healing.

- Have I or my organisation been reluctant to engage with victim-survivors out of fear of defamation, lawsuits, or damages to reputation?

- Have I benefited from those individuals who have spoken out about wrongful behaviour, but not shown public or private support out of fear?

- Have I questioned (publicly or privately) the practices of the group in question; their power, resources, and control mechanisms?

- Have I contacted victim-survivors who I may know, and shown my support for their courage?

- Have I made an effort to question how my own organisation is in a position of power that can provide support?

- Have I considered ways that I can challenge the constructs of power operating (covertly or overtly)?

- Have I acknowledged the inherent risk and danger to safety, livelihood, and well-being that the victim-survivor has endured in order to speak out, raise public awareness and prevent other people from being hurt?

Cult specialists, support services & further information

Cult Consulting Australia provides exit counselling, legal support in cult-related court matters, government liaison and research.

Cult Information and Family Support are an Australian support and information network formed by loved ones of those involved in abusive cults. The website includes a range of books written by those with lived experience of cults and personal stories from cult members.

Carli McConkey is a cult survivor and author of the book, The Cult Effect. Her website includes support services for the USA, France, UK, Canada, and Australia. Along with information on cults, her personal story, and resources to relevant journal articles on cults within Australia.

Freedom of Mind is an American-based organisation, founded by Dr. Steven Hassan offering coaching, consulting training, and education. Their website includes an extensive list of resources, including videos from leading experts on cults and an international support list, and a paid course on cult education.

Revolt Against Cults is an Australian not-for-profit providing free educational material on cults within Australia. Helpful pdf’s listed on their website include, the methodology of cult groups, activities and behaviours that occur within cult groups, and a list of cult groups within Australia.

Integrative Psychology Nigel Denning comes highly recommended and is regarded as an experienced Australian Counselling Psychologist working out of Integrative Psychology in Melbourne, Australia.

International Cultic Studies Association has a useful section for former members with an extensive reading list, including post-cult after-effects and religious and spiritual abuse.

Documentaries/docu-series available via streaming platforms

- Orgasm Inc: The Story of One Taste (Netflix)

- Wild, Wild Country (Netflix)

- Leah Remini: Scientology and the Aftermath (Stan)

Books

- Do As I Say – Sarah Steel

- Uncultured – Daniella Mestyanek Young

- Beyond Belief – Jenna Miscavige Hill

- Free e-books are available through the International Cultic Studies Association, including books on recovery from abusive groups

Short Youtube Videos

- What is a cult and how does it work? – Margaret P Singer, PhD

- Leaving a cult – Margaret P Singer, PhD

Other checklists on cultic groups

A comprehensive list of support services by Australian state and territory has been compiled by Revolt Against Cults and is accessible here.

References

Agetue, N. F., & Ogodu, O. J. (2022). Cultism and Peaceful/Safe Campuses in Nigerian Tertiary Institutions. Journal of Public Administration, Finance & Law, 24, 31–41. https://doi.org/10.47743/jopafl-2022-24-03

Best, J. V. C, (2018). Cults: A Psychological Perspective. Columbus State University, USA

Burke, J. (2006). Antisocial Personality Disorder in Cult Leaders and Induction of Dependent Personality Disorder in Cult Members. Cultic Studies Review, 5(3), 390-410.

Buxant, C. & Saroglou, V. (2008). Joining and leaving a new religious movement: A study of ex-members’ mental health, Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 11(3), 251-271, doi:10.1080/13674670701247528

Cialdini, R (1984). Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion. Pymble, Australia: HarperCollins e-books

Coates, D. (2009). Post-Involvement Difficulties Experienced by Former Members of Charismatic Groups. Journal of Religion and Health, 49(3), 296-310. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10943-009-9251-0

Collins, G., (1982). The psychology of the cult experience. PSYCHOLOGY, 58, 19 < https://www.nytimes.com/1982/03/15/style/the-psychology-of-the-cult-experience.html

Dittmann, M. (2002). Cults of hatred: Panellists at a convention session on hatred asked APA to form a task force to investigate mind control among destructive cults. American Psychological Association, 33(10).

Dussuyer, I., Smith, R.G., Armstrong A. & Heenetigala, K. (2018). Understanding and responding to victimisation of whistleblowers. Australian Institute of Criminology https://www.aic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-05/23-1314-FinalReport.pdf

Dupuis, D. (2021). Psychedelics as Tools for Belief Transmission. Set, Setting, Suggestibility, and Persuasion in the Ritual Use of Hallucinogens. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.730031

Ellwood, R. (1986). The several meanings of cult. Thought. 61(2), 212–224. https://doi.org/10.5840/thought19866123

Galanter, M. (1999). Cult’s faith, healing, and coercion. New York: Oxford University Press.

International Cultic Studies Association. (n.d). FAQs – What is a cult?. https://www.icsahome.com/elibrary/faqs#h.p_ID_160

Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs. (2000).Conviction with compassion: A report into freedom of religion and belief. Canberra: AGPS

Kennedy H (2004). Foreword, in Calland R & Dehn G (eds), Whistleblowing around the world: Law, culture and practice. Cape Town: Open Democracy Advice Centre; London: Public Concern at Work, https://www.aic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-05/23-1314-FinalReport.pdf

Kern, C., & Jungbauer, J. (2022). Long-Term Effects of a Cult Childhood on Attachment, Intimacy, and Close Relationships: Results of an In-Depth Interview Study. Clinical Social Work Journal, 50(2), 207–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-020-00773-w

Kriegman, D., & Solomon, L.. (1985). Cult Groups and the Narcissistic Personality: The Offer to Heal Defects in the Self. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 35(2), 239–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207284.1985.11491415

Lalich, J., & Tobias, M. (2006). Take back your life: Recovering from cults and abusive relationships. Bay Tree Publishing.

Lifton, R.J (1961). Thought reform and the psychology of totalism: A study of ‘brain washing’ in China. The University of North Carolina Press.

Maccoby, M. (2004). Narcissistic Leaders: The Incredible Pros, the Inevitable Cons. Harvard Business Review, 1, 69-77.

Meyer, H. (2022, September 5). “What makes a cult a cult?” The Tennessean. https://www.tennessean.com/story/news/religion/2016/09/15/what-makes-cult-cult/90377532/.

Oakes, L. (1997). Prophetic Charisma: The psychology of revolutionary personalities. Syracuse University Press.

O’Reilly, C. A., & Chatman, J. A. (2020). Transformational Leader or Narcissist? How Grandiose Narcissists Can Create and Destroy Organizations and Institutions. California Management Review, 62(3), 5–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008125620914989

Pignotti, M. (2000). Helping survivors of destructive cults: Applications of Thought Field Therapy. Traumatology, 6(3), 201–235. https://doi.org/10.1177/153476560000600304

Rajesh, S., Bohra, O., Marks, J., & Davis, A. (2022, September 9). “Psychedelics: A Tragic History of Cults, Drugs, and Promises to the Future” Medium. https://ucbneurotech.medium.com/psychedelics-a-tragic-history-of-cults-drugs-and promises-to-the-future-121ad2bd2b48.

Steel, S. (2022). Do as I say, (pp. 42-228) Macmillan.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (2004). The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior. In J. T. Jost & J. Sidanius (Eds.), Political psychology: Key readings (pp. 276–293). Psychology Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203505984-16

Tedeschi, R & Calhoun, L.G. (2004). Posttraumatic Growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry, 15(1) 118 ,DOI: 10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01

Tilgner, L., Dowie, T.K., & Denning, N. (2015). Recovery from church, institutional and cult abuse: A review of theory and treatment perspectives. Integrative Psychology. http://www.leavingshivayoga.guru/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/institutional-abuse.pdf

Turner, J. & Reynolds, K (2012). Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology: Self Categorization Theory. SAGE Publications Ltd. London. 399-417. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781446249222.n46

Van Vugt, M., Hogan, R. & Kaiser, R. (2008). Leadership, followership, and evolution: Some lessons from the past. The American Psychologist, 63(3), 182-96. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.63.3.182

Young, J. L., & Griffith, E. E. (1992). A critical evaluation of coercive persuasion as used in the assessment of cults. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 10(1), 89-101.